MeesterDaan (talk | contribs) (→Gelb's Hypothesis: from pictures to sounds) |

MeesterDaan (talk | contribs) (→Kanjis correspond to sounds too) |

||

| Line 78: | Line 78: | ||

|- | |- | ||

|valign="top"| | |valign="top"| | ||

| − | So it seems that | + | So it seems that successive disappearance of visual features accounts for the clustering found in the network of Kanji. In other words: Kanji have become simpler through time. They are nowhere near the elaborate pictures they were around 2,000 years ago, but in many ways symbolic abstractions of their ancient precursors. |

| − | In the mean time, there is some evidence that certain components | + | In the mean time, there is some evidence that certain components correlate closely to a Kanji's pronounciation. Studies by Townsend (2011) and Toyoda, Fardius and Kano (2013) have yielded large sets of components that can be used by students to guess their pronunciation. For instance: many of the characters containing the 'middle'-component have a pronunciation "chuu", and many Kanji with the 'orders'-component have a pronunciation 'rei'. Yet, many of these Kanji sharing such an indicative component seem a world apart when it comes to their meaning. Why do the Kanji for mushroom, wise, bell and actor all have an order-component? Is there really a shared meaning in these characters? Or is it imaginable that these meaningful components have actually taken on somewhat of an alphabetic function? |

| − | We think they have, and as such regard | + | We think they have, and as such regard small-worldness in Japanese Kanji characters as a byproduct of a language going through a Gelbian phase transition. Most ancient writing systems began as series of pictures, but most of them have either transformed to an alfabetical system, or have disappeared. Japanese, a rarity in linguistics, is still in the midst of this transformation, and complex network analysis provide the tools to quantify the transformation, and explain why the Japanese is as it is today. |

| − | + | ||

|valign="top" |[[Image:kanji_evolution.jpg|frame|Kanji evolution through time. Notice how visual similarity has increased, especially between 'horse' and 'fish'. Adapted from [https://www.tofugu.com www.tofugu.com]]] | |valign="top" |[[Image:kanji_evolution.jpg|frame|Kanji evolution through time. Notice how visual similarity has increased, especially between 'horse' and 'fish'. Adapted from [https://www.tofugu.com www.tofugu.com]]] | ||

Revision as of 22:33, 18 February 2018

Contents

Paper

I'm still working on this page, but our paper is here. I (Daan van den Berg) welcome all feedback you might have. Look me up in the UvA-directory, on LinkedIn or FaceBook.

Japanese Kanji Characters

|

The whole idea was quite simple actually, born from the language enthousiasm of three programmers. But Japanese is not an easy language of choice, as it features a 60,000-piece character set named Kanji. Although you 'only' need to learn about 2,000 to read the language, this is still a formidable exercise in itself. There is some systematicity though, as many Kanji are composed of one or more of 252 components, and some combinations are more common tha others. Individual Kanji-characters are said to carry meaning in a word-like manner, and akin to how compound words are built up ("swordfish", "snowball", "fireplace"), kanji often derive meaning from the combination of components, and are thus often explained as such in textbooks for Japanese children and foreign students of the language.

|

Kanjis & Small-Worlds

|

The network of connected Kanji turned out to be a small-world network, which means it has a high clustering coefficient, a low average path length and a low connection density. At the time, computational linguists had already found a large number of small-world networks in different languages on various levels, but this network of Kanji sharing components was not yet one of them.

|

The functional connectivity graph of the brain is one of many well known small-worlds See Sporns & Honey (2006) and others. Image adapted from Sporns' book "Discovering the Human Connectome" |

Clustering Coefficient & Average Path Length (optional)

|

First let's have a brief look at what makes a small-world network a small-world network. First of all: small-world networks are sparse networks, that is, networks with relatively few edges. Second, small-world networks have a high clustering coefficient. The clustering coefficient on a vertex is the fraction of edges between its neighbours. As an example, look at the figure. Vertex C has four neighbours and between these four we have three edges, out of a possible six, so the clustering coefficient on C is 0.5. Similarly, the clustering coefficient on B is 1, and on F it is 0.33 if we disregard the two neighbours it must have outside the figue. If we don't disregard those, it has five neighbours with either one or two connections between them, so the clustering coefficient on F would be either 0.1 or 0.2. The cluster coefficient of the network is simply the average of all its vertices.

|

Gelb's Hypothesis: from pictures to sounds

|

Many language networks have small-world properties but for Japanese Kanji, there's a little more to it. There's an old conjecture by Ignacy Jay Gelb (1907-1985) and it appears to coincide with our findings. An American linguist from Polish descent, Gelb conjectured that all written languages go through a phase transition from being picture-based to being sound-based. Studied in more detail, the idea is quite coarse and the exact trajectory might differ from language to language, but the core concept remains alluring, especially where it concerns Japanese Kanji.

|

Ignace Jay Gelb (1907-1985), and his hypothesis as visualized by Tadao Miyamoto in his 2007-paper. Note how these initially quite pictorial characters in this Cuneiform script evolve to a set of characters built up from relatively repetitive components. |

Kanjis correspond to sounds too

|

So it seems that successive disappearance of visual features accounts for the clustering found in the network of Kanji. In other words: Kanji have become simpler through time. They are nowhere near the elaborate pictures they were around 2,000 years ago, but in many ways symbolic abstractions of their ancient precursors.

|

Kanji evolution through time. Notice how visual similarity has increased, especially between 'horse' and 'fish'. Adapted from www.tofugu.com |

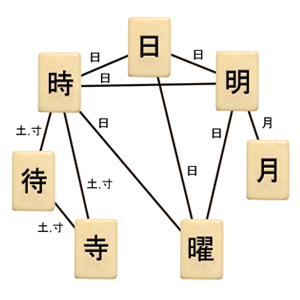

These seven characters all share a visual component, and a pronunciation ("rei"). Although Kanji meaning are often explained through combined components, this explanation looks unconvincing in some cases. Do components really add an element of meaning to a Kanji? Or is it actualy an element of sound? |

The Team

|

More

Maybe later.